Misinformation Investigation: A Practical Guide to Debunking Myths with Kids

Dr. Carla Engelbrecht is an expert in educational technology and CEO and Founder of Betweened, expertly curated, family-friendly entertainment (iOS and Android). Her writing focuses on helping caregivers connect with kids through technology.

Alarm bells rang when my 13-year-old daughter offhandedly remarked, “Did you know no one was born on December 6, 2006?”

My skepticism kicked in, considering the statistical improbability. Nonchalantly, I responded, “Really? Where’d you hear that?”

“Google.”

Jackpot. A perfect teachable moment. “Which sources does Google reference?”

“I dunno.”

“Probably worth checking that, right? To know whether Google is using reputable sources?”

She sighed, likely thinking, “Why can’t mom just let me enjoy fun facts without questioning them?”

So how did we break it down this little nugget of misinformation?

Step 1: Identify the Source

We Googled “Was no one born on December 6, 2006?”

The results were primarily TikTok videos, with no debunking articles from reliable sites like Snopes.com. The only factual reference was a random database listing 3,000 entries. Hardly a global population.

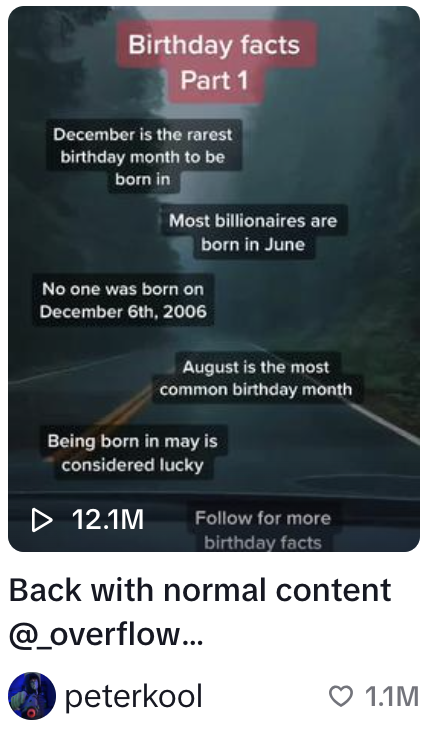

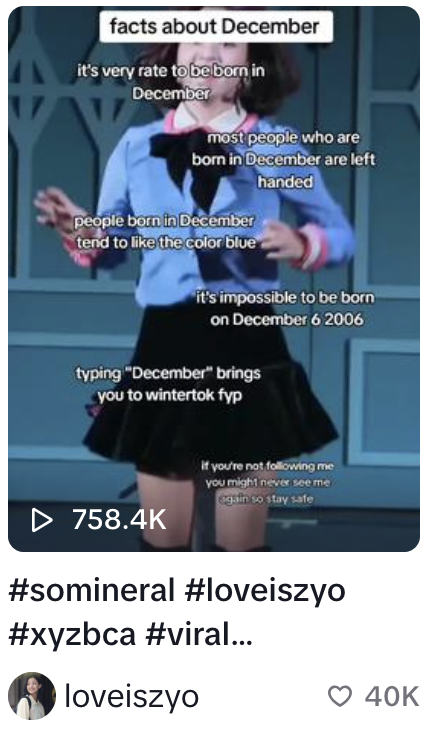

The TikTok search page showed dozens of videos with a series of “Birthday Facts,” one with 12 million views and many with thousands of views.

The claims included:

“December is the rarest month to be born in”

“Most billionaires are born in June”

“No one was born on December 6th, 2006”

“August is the most common birthday month”

“Being born in May is considered lucky”

The same “facts” appear in most of the videos. No sources. Notably, the comments include quite a few people sharing their birthday of December 6, 2006.

Step 2: Assess the Statistical Possibility

Is it even statistically possible for no one to be born on a given day? In short, no. But we needed to walk through the logic. ChatGPT4 helped break this down. (The transcript is here.)

I first prompted, “What are the odds that no one is born on a single day?”

After explaining how to use the birthday problem framework, ChatGPT calculated that there’s 8% chance that no one in a group of 1,000 people has a birthday on a specific day.

Interesting, but not exactly what I was asking. So I changed the prompt to be more specific.

“Here's why I'm asking. My daughter saw a TikTok that said no one was born on Dec 6, 2006. I'm trying to help her understand the statistical improbability of that happening, as part of understanding the importance of thinking critically about information you see online.

So... can you calculate the probability that no one was actually born -- globally -- on Dec 6, 2006?”

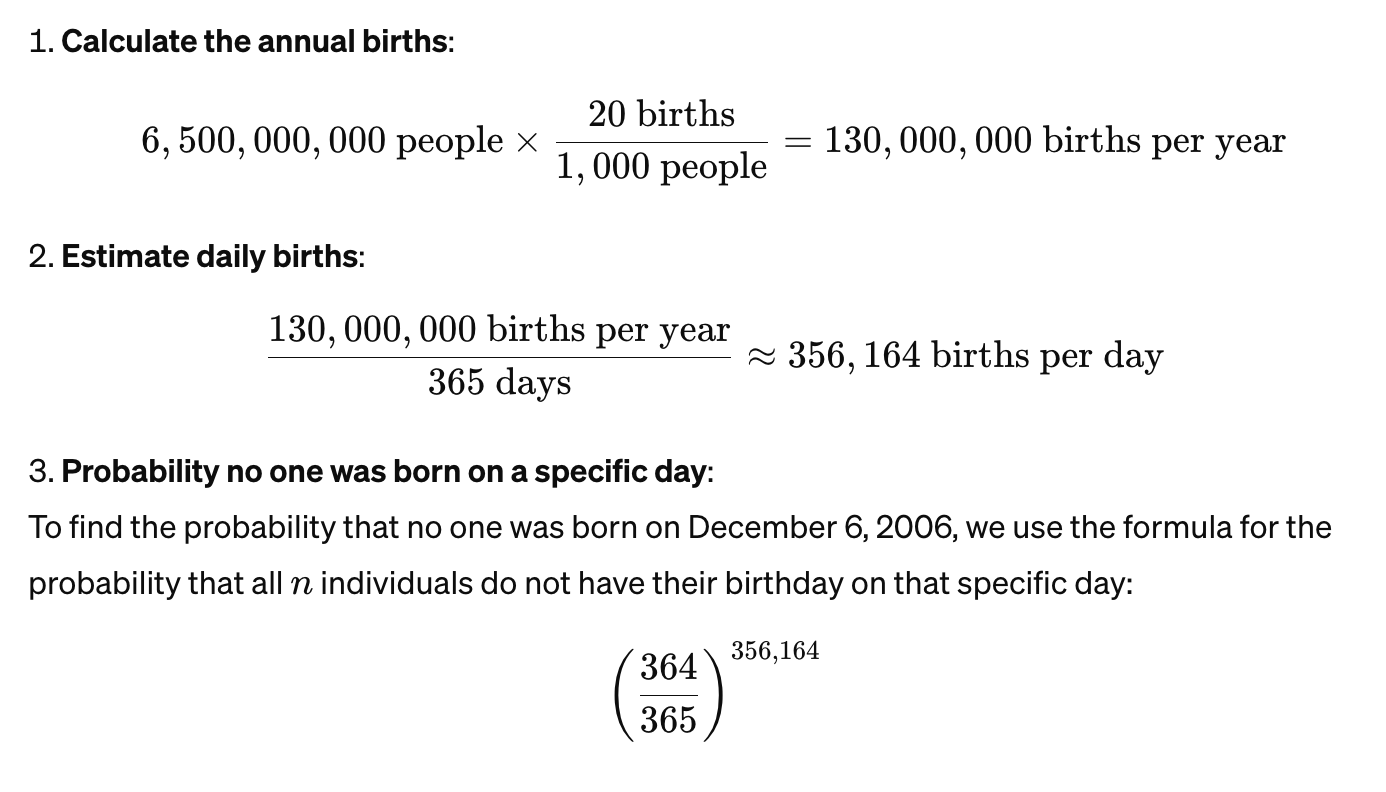

ChatGPT then proceeded to estimate the annual births, daily births, and the probability that all of the individuals do not have the birthday on a specific day.

ChatGPT’s calculations of probability that no one was born on a specific day.

It returned: “The calculated probability that no one was born globally on December 6, 2006, is effectively zero. This means it's extremely unlikely—practically impossible—that there were no births worldwide on that specific day.”

Phew. That was a lot of work, considering it was originally from a 30 second statement.

Why does misinformation like this spread so easily?

Two descriptions for you -- one for adults and one to use with kids.

For adults

Misinformation occurs due to a variety of complex factors that intersect with human psychology, technology, and social dynamics. At its core, misinformation is false or inaccurate information that is spread unintentionally. It often arises from:

Cognitive Biases: Humans have a tendency to accept information that aligns with their preexisting beliefs or biases—a phenomenon known as confirmation bias. This predisposes individuals to believe and share information without verifying its accuracy if it supports their views.

Social Media Algorithms: Platforms are designed to maximize engagement, leading algorithms to prioritize content that is sensational or emotionally charged, regardless of its truthfulness. This often results in the amplification and rapid spread of misinformation.

Information Overload: The sheer volume of information available today makes it difficult to verify every piece of data we come across. In this flood, false information can spread quickly, as people might not take the time to critically evaluate its validity.

Echo Chambers: Online and offline communities often create echo chambers where dissenting views are excluded, and only agreeing perspectives are amplified, further entrenching misinformation.

Misinformation can have serious consequences, including influencing public opinion and policy, inciting panic, and undermining trust in credible institutions and experts.

For kids

Think of misinformation like a game of "telephone," where one person whispers a message to the next, and by the time it reaches the last person, the message has changed a lot. This happens with stories or facts people share, too. Here’s why:

Mistakes: Sometimes, when people try to tell a story they heard, they accidentally change some parts because they didn’t remember it right or they misunderstood. It’s like when you try to draw a picture from memory; sometimes, it doesn’t look exactly like the original.

Fast Sharing: When people find something interesting or surprising, they often share it quickly with others without checking if it’s true. It’s like when you're excited to tell your friend about a cool bug you saw, but maybe you mix up what kind of bug it was because you told the story so fast.

Following Others: Sometimes, people believe something just because a lot of other people believe it or because it’s a story from someone they think is usually right. It’s like when you think something must be good because your best friend said it’s good.

It's important to ask questions and think about whether what you’re hearing makes sense or if it's true, just like in school when you double-check your answers.

Reinforcing Critical Thinking

We spent 30 minutes dissecting a claim that took 30 seconds to make an impression. Misinformation isn’t new, but it is far easier to pass along now. It’s frustrating to me as a parent, but I also have to remember that often my role is to help model critical thinking by

Listening for questionable statements.

Asking probing questions about the likelihood and sources.

Researching together, from checking sources to analyzing probabilities.

Reminding our kids that we all make mistakes and fall for misinformation

Not every statement needs to lead to an extended conversation. Sometimes it’s enough to simply say, “that doesn’t sound right to me,” in order to plant the critical thinking seeds. Checking out the professional misinformation detectives on Snopes.com or watching Mythbusters can also lead to great conversations and enjoyable entertainment.

Dr. Carla Engelbrecht is a highly-selective mom, product leader, and internationally recognized expert on children’s education and entertainment technology. As founder of Betweened, she's on a mission to transform entertainment for kids and their families. If you haven’t already, sign up for the newsletter to get more articles like this or enjoy our free 60 minute video on how to manage when technology goes sideways.